Allergies

Biting Insect Allergy: Mosquitoes, Flies, and Kissing Bugs

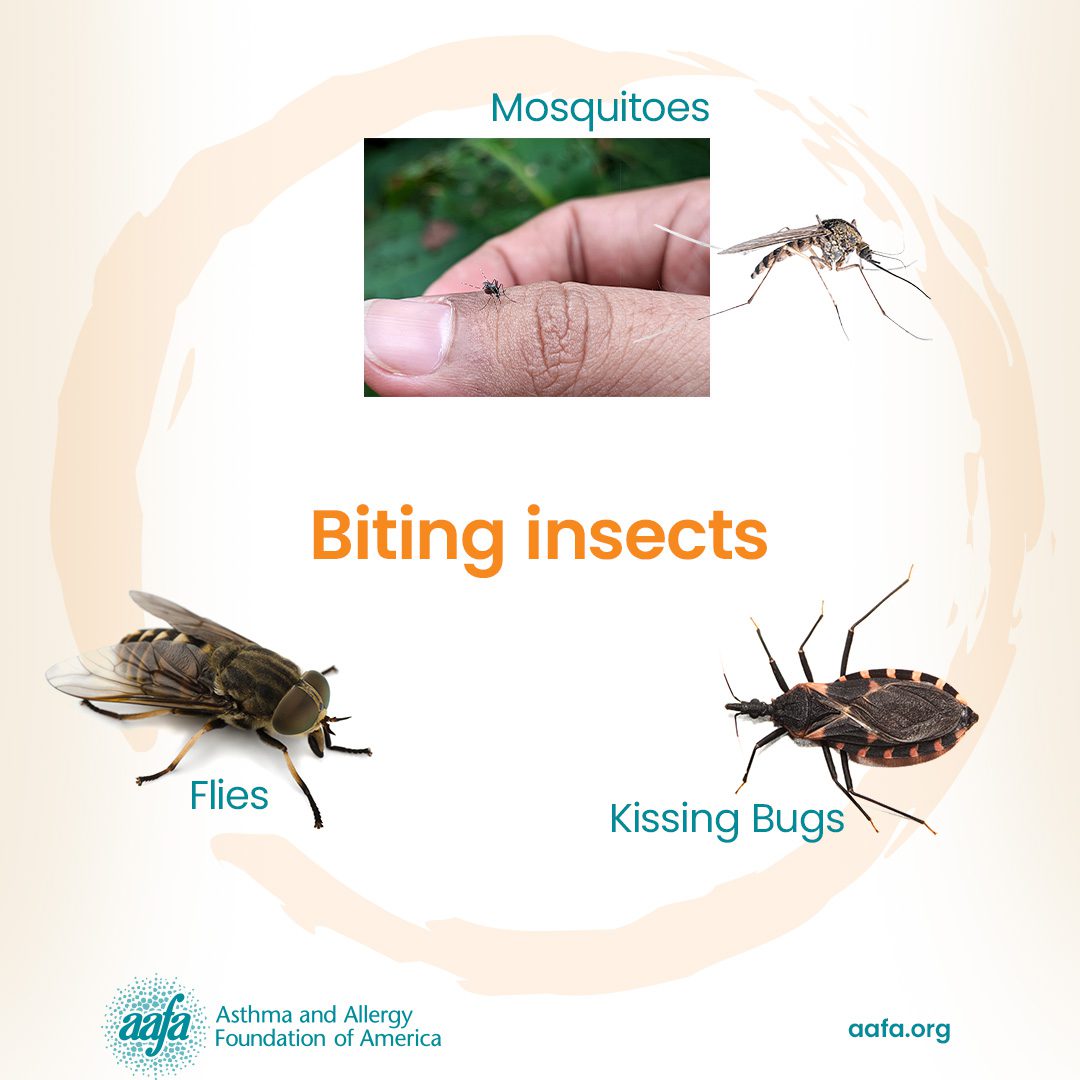

Mosquitoes and flies are common biting insects that live in many locations around the world. Kissing bugs can be found in in the southern United States, Mexico, Central America, and South America. Mosquitoes, flies, and kissing bugs bite humans to feed on their blood.1

Most people bitten by insects suffer pain, redness, itching, and minor swelling in the area around the bite. Mosquito, fly, and kissing bug bites can also cause allergic reactions.1

On this page:

What is mosquito, fly, or kissing bug allergy?

What are the symptoms of biting insect allergy?

How do doctors diagnose biting insect allergy?

What is the treatment for biting insect allergy?

How can I prevent allergic reactions to mosquitoes, flies, and kissing bugs?

How can I identify mosquitoes, flies, and kissing bugs?

What Is Mosquito, Fly, or Kissing Bug Allergy?

When a mosquito, a fly, or a kissing bug bites a person, its saliva transfers allergens into the person’s bloodstream. An allergen is a substance that causes an allergic immune reaction.1

Activities such as hiking, camping, working with animals, and visiting farms and forested areas can increase your chances of getting bug bites. Other risk factors for bug bites include wearing clothes with exposed arms or legs or having open food or drinks.2,3

Mosquitoes bite men more than women, and children more than adults, likely relevant to time spent outdoors. A warmer body temperature, breath odors, and sweating may also increase the chance of mosquito bites.4

Flies, including horseflies and black flies, are commonly found near sources of water. Flies can bite humans and other mammals. This can lead to irritation, infection, various diseases, and sometimes an allergic reaction.

Kissing bug bites occur more often in people living in geographic areas with warm and humid weather. Crowded houses, and construction materials such as dirt flooring, and cardboard tile, are also factors associated with a higher chance of existence of kissing bugs.5 Kissing bug bites can cause Chaga’s disease. Allergic reactions to kissing bug bites are rare or uncommon.

What Are The Symptoms of Biting Insect Allergy?

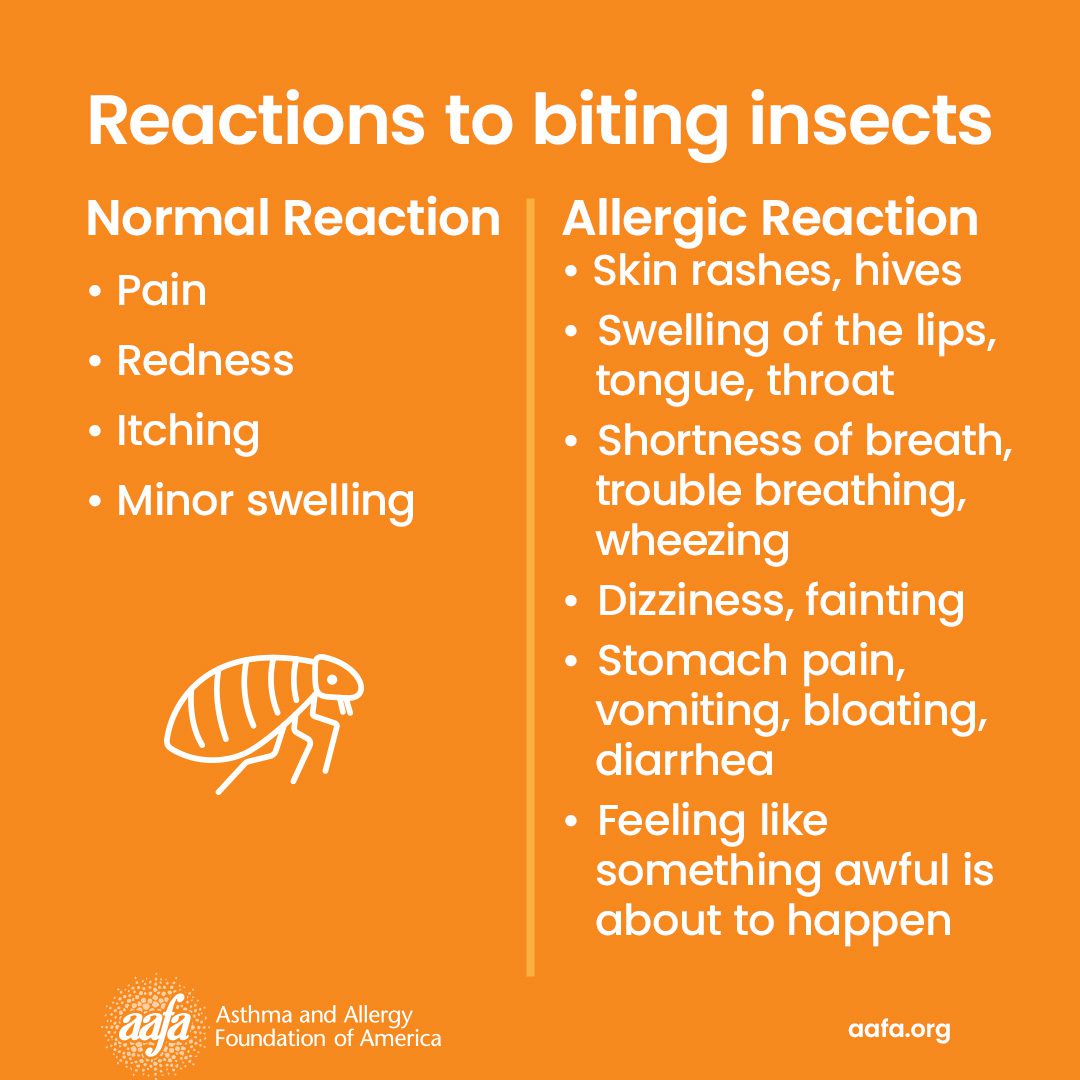

Most people who get bit by insects may suffer pain, redness, itching, and minor swelling in the area around the bite. This is a normal reaction. Most people get better within hours or days.

If you are allergic to mosquitoes, flies, or kissing bugs, these insects’ bites can cause localized reactions such as hives or rash. The affected area may also swell, and a blister may appear. Scratching the blister and the affected area may lead to infections. Sometimes symptoms can be systemic, which means they can affect the entire body and not just the area of the bite.1

Skeeter syndrome is a large local allergic reaction to mosquito bites. People with skeeter syndrome usually develop significant inflammation, large areas of swelling, itching, fever and possibly blisters, starting about 8 to 10 hours after the mosquito bite. The swelling may become severe, and people may experience trouble moving a hand or a foot, for example, if the swelling crosses the wrist or ankle. The symptoms usually resolve in 3 to 10 days. Skeeter syndrome affects mainly children, older adults, and people with impaired or undeveloped immunity levels.6,7

However, on rare occasions, people can have a serious allergic reaction to bug bites. A life-threatening allergic reaction (anaphylaxis [anna-fih-LACK-sis]) produces signs and symptoms that require immediate medical attention. Without immediate treatment, anaphylaxis may cause death. Symptoms usually involve more than one organ system (part of the body), such as the skin or mouth, the lungs, the heart, and the gut. Some symptoms include:1

- Skin rashes, itching, or hives

- Swelling of the lips, tongue, or throat

- Shortness of breath, trouble breathing, or wheezing (whistling sound during breathing)

- Dizziness and/or fainting

- Stomach pain, vomiting, bloating, or diarrhea

- Feeling like something awful is about to happen

How Do Doctors Diagnose Biting Insect Allergy?

To diagnose a biting insect allergy, your doctor may give you a physical exam and discuss your symptoms and your history of allergic reactions to insects. The identification of the insect can also be helpful.1

If your doctor thinks you have a biting insect allergy, they may suggest a skin or blood test.8

Skin Prick Test (SPT). In prick/scratch testing, a small drop of the possible allergen is placed on your skin. Then the nurse or doctor will lightly prick or scratch the spot with a needle through the drop. If you are allergic to the substance, you will develop redness, swelling, and itching at the test site within 20 minutes. You may also see a wheal. A wheal is a raised, round area that looks like a hive. Usually, the larger the wheal, the more likely you are to be allergic to the allergen.

A positive SPT to a particular allergen does not necessarily mean you have an allergy. Health care providers must compare the skin test results with the time and place of your symptoms to see if they match.

Specific IgE Blood Test. Blood tests are helpful when people have a skin condition or are taking medicines that interfere with skin testing. They may also be used in children who may not tolerate skin testing. Your doctor will take a blood sample and send it to a laboratory. The lab adds the allergen to your blood sample. Then they measure the amount of antibodies your blood produces to attack the allergens. This test is called Specific IgE (sIgE) Blood Testing (this was previously and commonly referred to as RAST or ImmunoCAP testing). As with skin testing, a positive blood test to an allergen does not necessarily mean that an allergen caused your symptoms.

What Is the Treatment for Biting Insect Allergy?

If you get bit by a mosquito, fly, or kissing bug, gently wash the bite site with soap and water to prevent infections. Do not scratch or break blisters.1

Most insect bites need only supportive care with over-the-counter medicine. Applying a corticosteroid [kor-tick-OH-stair-ROID] (usually hydrocortisone) cream to the bite site is usually enough to relieve the localized symptoms such as itching and swelling. An oral antihistamine can also be helpful to relieve itching. An oral pain reliever (such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen) may also be helpful. The localized pain and swelling may also be improved by applying a cold compress and by raising the affected limb. These measures are usually helpful to manage and treat cases of skeeter syndrome, resulting from mosquito bites. However, if a person develops a severe case of skeeter syndrome, systemic corticosteroids may also be prescribed.1,7

Some reactions may become severe and cause systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis. If you experience symptoms like severe chest pain, nausea, sweating, shortness of breath, severe swelling, or slurred speech, you should immediately seek medical care.1

Epinephrine [ep-uh-NEF-rin] can reverse severe systemic reactions and is the most important treatment available for anaphylaxis. If you have a severe allergy to insect bites, you should carry an easy-to-use form of epinephrine. You should also consider wearing a medical identification bracelet or necklace containing information about your allergy.1

How Can I Prevent Allergic Reactions to Mosquitoes, Flies, and Kissing Bugs?

The best way to prevent allergic reactions to mosquitoes, flies, and kissing bugs is to prevent these insects’ bites.1

Use effective insect repellents. DEET (N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) is the most used and is recognized by the World Health Organization as the gold standard insect repellent. Picaridin and PMD (P-menthane-3,8-diol) can also be used as alternatives to DEET.1 However, DEET and picaridin should not be used on children under 2 years old, and PMD should not be used on children under 3 years old.2,6 When outdoors consider wearing light-colored clothes, and long-sleeved shirts. Hats can also be helpful to avoid insect bites. Mosquito nets are highly effective in preventing bites from insects. For example, these can be used to cover you while you sleep, or cover strollers and baby carriers. Consider using shoes, clothes, and mosquito nets previously treated with permethrin (an insecticide). When travelling, stay in well-built places like a hotel or lodging with air conditioning or window and door screens.1,2,6

How Can I Identify Mosquitoes, Flies, and Kissing Bugs?

Mosquitoes have compound eyes, one pair of delicate wings, long thin legs, a slender body, and an elongated tube-shaped mouthpart used for biting and feeding on blood. Mosquitoes can be found everywhere on every continent in the world, except Antarctica. These insects are known to thrive and reproduce in wet environments. Adult mosquitoes can be found both indoors and outdoors. These insects can bite day and night. Some species of mosquitoes are known to be able to transmit viruses or parasites that cause diseases to humans and animals.1,9

Flies have small and stout bodies, large compound eyes, a pair of membranous wings, and three pairs of short legs. The color varies depending on species. When obtaining a blood meal, flies use their mouthparts to tear the skin. Flies can be found worldwide. There are several species of flies that bite humans, namely the deer fly, horse fly, sand fly, and tsetse fly. These insects are usually attracted by moist organic material, such as garbage, manure, and dead animals, upon which they lay their eggs and feed. Thus, flies can contaminate human foods and food preparation surfaces by landing on them.1,10

Kissing bugs, or triatome bugs, have brown or black, slightly flat and “tear drop” shaped bodies, with long and thin legs, and red or yellow stripes on their abdomen. These insects have a very long tube-shaped mouthpart that is kept folded under their head when the insect is not feeding. Kissing bugs are blood-sucking insects, that usually hide during the day and come out at night to feed on people. These insects can be found in southern United States, Mexico, Central America, and South America where they typically live in thatched roofs, cracks, and holes of inadequate housing. Kissing bugs can transmit a parasite that causes Chagas disease.1,11

Closed

References

- Powers J, & McDowell RH. (2023, August 8). Insect Bites. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537235/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, May 11). Avoid Bug Bites. Travelers’ Health. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/avoid-bug-bites

- Bon Secours. (n.d.). Insect Bites and Stings. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://www.bonsecours.com/health-care-services/primary-care-family-medicine/conditions/insect-bites-and-stings

- Seattle’s Children. (2025, January 25). Mosquito Bite. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://www.seattlechildrens.org/conditions/a-z/mosquito-bite/

- Medina-Torres I., Vázquez-Chagoyán J. C., Rodríguez-Vivas R. I., & de Oca-Jiménez R. M. (2010) Risk factors associated with triatomines and its infection with Trypanosoma cruzi in rural communities from the southern region of the State of Mexico, Mexico. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 82(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.08-0624

- Vander Does A., Labib A., & Yosipovitch G. (2022). Update on mosquito bite reaction: Itch and hypersensitivity, pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment. Frontiers in Immunology, 21(13), 1024559. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1024559

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022, June 13). Skeeter Syndrome. My Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23289-skeeter-syndrome

- American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. (2019, June 27). Immunotherapy for mosquito allergy. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://www.aaaai.org/allergist-resources/ask-the-expert/answers/old-ask-the-experts/mosquito

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, May 14). About Mosquitoes. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/about/

- Illinois Department of Public Health. (n.d.). The House Fly and Other Filth Flies. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://www.idph.state.il.us/envhealth/pcfilthflies.htm

- University of Texas, UTHealth School of Public Health. (n.d.). Kissing Bugs & Chagas Disease. Retrieved May 9, 2025, from: https://www.dshs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/IDCU/disease/chagas/UT_Health_Kissing_Bug_Chagas_Guide-061918.pdf

Med Communications, Inc. assisted with development and review of medical content. Medical review: May 2025 by Jeffrey G. Demain, MD.